Arbitrators, Adjudicators and GDPR is it YK2 all over?

Arbitrators, Adjudicators and GDPR is it YK2 all over?

It is all about personal data right!

My name is Simon Tolson and I will be speaking about GDPR a subject I profess to be no expert in and a mere amateur!

By way of background, I have been in practice for well over 30 years and I joined Fenwick Elliott nearly 32 years ago in 1987 and have been senior partner now for the last 16 years. I specialise particularly in construction law and I have often been asked to advise on things I know little about! GDPR amongst them!

Let’s get one thing straight at the start, the General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679 (“GDPR”) does not apply to people processing personal data in the course of exclusively personal or household activity. This means you would not be subject to the Regulations if you keep personal contacts’ information on your computer or you have CCTV cameras on your house to deter intruders, as processing carried out by individuals purely for personal/household activities is not circumscribed. But if you are a business then take caution1. I am sure you will have been inundated with consultants offering to keep you safe just as the vultures descended in 1999 on the date change at Y2K and few lost a sock let alone a shirt over it.

What personal data?

Personal data2 relates to information of an identifier (“Data subject”) which can be obtained either offline (such as name, location, mental, economic or social identity of a natural person) or online (such as internet protocol address, cookie identity etc). The data processor3 is a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body which processes personal data on behalf of the data controller, who determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data4.

The broad definition of “data subjects”5 contained in the GDPR means they a "natural individuals” drill a bit further and every person holding the nationality of a Member State shall be a citizen of the Union (per Article 20 (1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union).

And it applies to all data controllers and data processors who are located in the EU or, if they are not in the EU, who process data of individuals who are in the EU, where the processing activities are related to the offering of services (i.e. arbitration and adjudication) to such data subjects or the monitoring of their behaviour, as long as it takes place within the EU.

Taking account of the fact, solicitors, counsel, or a professional third party such as an expert, or an arbitral or adjudication institution or ANB can be considered data controllers or, in some cases, data processors, the GDPR applies potentially to many situations.

Adjudicators and arbitrators

GDPR may affect how an adjudicator or for that matter party representative gather documents to establish the facts of a case. While there are legal bases which allow for a proper processing of data without obtaining consent (e.g. legitimate interest), you in this room as practitioners will have to be aware and read up on these bases. Likewise, arbitration may well involve documents from third parties, and solicitors and counsel may have to deal with the processing of their personal data, too.

Adjudicators and Arbitrators / Tribunals and arbitral and adjudication institutions (in addition to companies selling arbitration databases) will have to ensure compliance with the GDPR.

As the recipients of data, tribunals will have the task of complying with one of the six different legal bases for the processing of personal data and respect the rights of the data subjects. The right of access, which is almost absolute, poses a particular challenge as a tribunal cannot in principle object to a request from an individual to see what information it has on him or her. Tribunals must also ensure that data is adequately protected.

The GDPR also poses challenges for institutions which keep databases on cases and adjudicators and arbitrators. It could be possible that miffed arbitrator or adjudicator, for example, might ask for access to the institution’s data following a challenge or might request to see a firm’s data on him or her to ascertain why he or she was not appointed in a particular case.

All those parties involved should prepare their Record of Processing Activities and include with all detail the specific contents established in the GDPR.

Another area GDPR of concern as we shall see below is the extent to which EU data protection rules might affect disclosure of documents in arbitration (and to a rather lesser extent adjudication).

The GDPR creates administrative, civil and, depending on each domestic legislation implementing the GDPR, potential criminal liability6 for those who breach it. Local independent institutions will be in charge of monitoring compliance with the GDPR. They may impose administrative fines up to 4% of annual turnover or €20 million (US$23.5 million), whichever is higher. Similarly,to the former Directive 95/46, the GDPR also provides that any person who has suffered damage is entitled to receive compensation. Member states can rule on other penalties, along or independently from the fines that can be imposed in all cases of infringement.

Who does the GDPR apply to?

- The GDPR applies to ‘controllers’ and ‘processors’.

- A controller determines the purposes and means of processing personal data.

- A processor is responsible for processing personal data on behalf of a controller.

- If you are a processor, the GDPR places specific legal obligations on you; for example, you are required to maintain records of personal data and processing activities. You will have legal liability if you are responsible for a breach.

- However, if you are a controller, you are not relieved of your obligations where a processor is involved – the GDPR places further obligations on you to ensure your contracts with processors comply with the GDPR.

- The GDPR applies to processing carried out by ‘organisations’ operating within the EU. It also applies to organisations outside the EU that offer goods or services to individuals in the EU.

To fall within the remit of the GDPR, the processing has to be part of an “enterprise”. Article 4(18) of the Regulation definesthis as any legal entity that is engaged in economic activity. Practicing as an adjudicator, QS, Architect, Engineer etc is engaging in economic activity. One must be careful not to mistake business conducted from home for household activity. So, all you one-man banders wake up!

That said, the GDPR broadly expects all small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to comply in full with the Regulation, but it makes some exceptions for organisations that have fewer than 250 employees.

The Regulation acknowledges that many SMEs pose a smaller risk to the privacy of data subjects than larger organisations. For example, Article 30 of the Regulation states that organisations with fewer than 250 employees are not required to maintain a record of processing activities under its responsibility, unless “the processing it carries out is likely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of data subjects, the processing is not occasional, or the processing includes special7 categories of data.

It is therefore very possible that you will need to disclose if you are an SMB, as you are only exempt from doing so if you only process EU residents occasionally.

One of six bases

A key principle in the GDPR is that data controllers need to process personal data lawfully, fairly and transparently.

Like the Data Protection Act 1998, the GDPR sets out the list of lawful justifications for processing - often referred to as the “conditions for processing”. But what is new under the GDPR is an explicit obligation to tell people the legal basis for processing their personal data. So you now have to document and communicate this.

Article 6(1) of the GDPR states that data processing shall be lawful only where at least one of the provisions at Article 6(1)(a)-(f) applies.

Remember: Adjudication is the legal process by which an ‘arbiter’ reviews evidence and argumentation, including legal reasoning set out by opposing parties or litigants to come to a decision which determines rights and obligations between the parties involved.

Another reason for needing to be clear about your lawful basis for processing personal data is that it affects the extent to which the individual can limit that processing. For example, if you are lawfully processing someone’s personal data because it is necessary for the performance of their employment contract, then they do NOT have the right to object to that processing.

The six bases or conditions for processing all types of personal data:

- The individual has given consent to the processing of his or her personal data for one or more specific purposes. Various further conditions apply where you wish to rely on consent as a lawful basis; see “Consent” section below.

- Processing is necessary for the performance of a contract to which the individual is party or in order to take steps at the request of the individual prior to entering into a contract.

- Processing is necessary for compliance with a legal obligation to which the controller is subject.

- Processing is necessary in order to protect the vital interests of the individual or of another natural person.

- Processing is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller.

- Processing is necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued by the controller or by a third party, except where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual which require protection of personal data, in particular where the individual is a child. Public authorities may not rely on this ground in the performance of their tasks; see “Public Authorities” below.

As Adjudicators and party reps for example these basis will be commonly prayed in aid will be:

- performance of a contract, including undertaking my instructions in a given matter;

- to comply with a legal obligation;

- to protect the vital interests of you or of another person (if a practicing lawyer);

- to perform a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in me;

- for the legitimate interests of you (as data subject), me (as data controller) or a third party

The lawful basis or bases upon which you may process ‘special category data’8

GDPR special category data includes the following information:

- Race and ethnic origin

- Religious or philosophical beliefs

- Political opinions

- Trade union memberships

- Biometric data used to identify an individual

- Genetic data

- Health data

- Data related to sexual preferences

is that such processing is necessary for the purpose of establishing, exercising or defending legal rights.

Consider as a party rep this example of a sound basis of justifying processing:

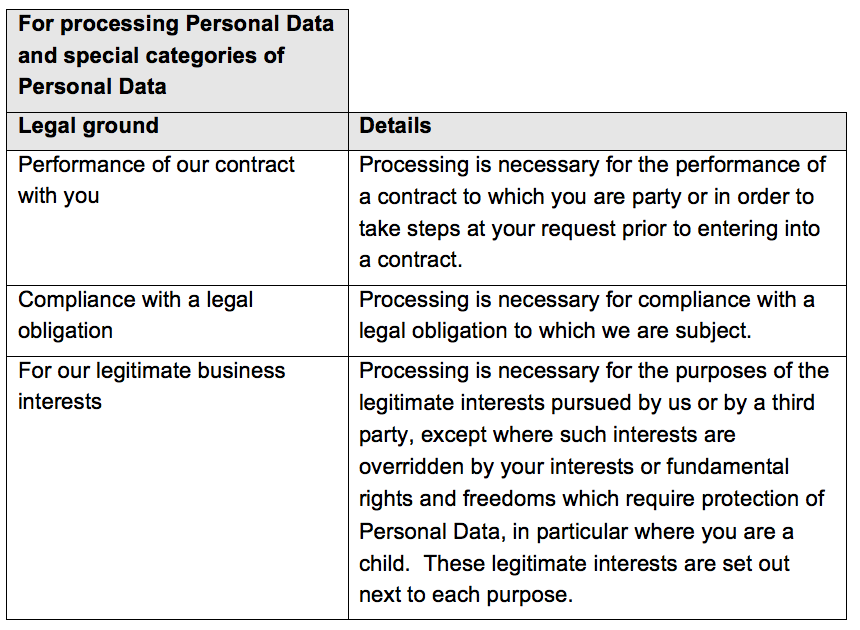

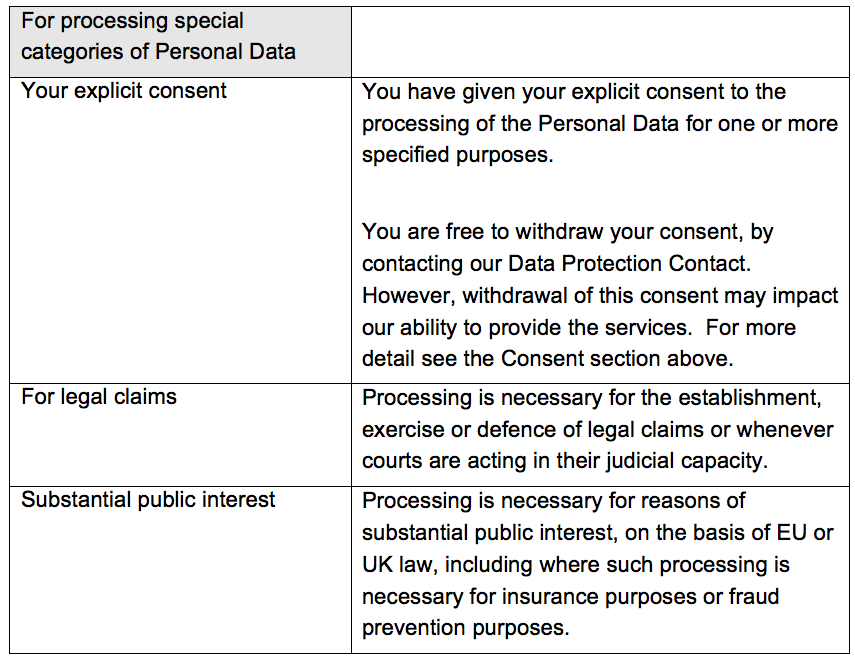

List of the legal grounds we rely may rely on:

How it kicked off

The GDPR of course came into force in all EU member states on 25 May 2018 without the need for any additional local legislation implementing it.

As regards the post-Brexit UK, in a recent paper entitled “Cyber Security Regulation and Incentives Review”, the Government confirmed that implementation of the GDPR will not be affected by the UK’s decision to leave the EU. But it should be borne in mind, in this regard, that even if the substance of the GDPR is maintained in English law post-Brexit, the UK will, technically, be a “third country”9 for these purposes.

At least in the short-term, all UK based organisations10 will have to adapt to the new requirements. It is also likely that any future developments in the UK’s regulatory approach towards cyber security will seek to maintain some form of equivalence with the EU’s model.

Hot topic

Data security is of course a red-hot topic at the moment. Pushing to one side the gaudy details of the Cambridge Analytica/Facebook debacle11, many lawyers, adjudicators and arbitrators have been focused on the (perhaps less electrifying but nonetheless important) provisions of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), no less so than since 25 May together with the Data Protection Act 2018 which came into force two days earlier.

Much has been printed about the GDPR and its potential consequences (and costs) for companies and individuals. The extensive duties placed on data controllers and processors, and the potential for significant penalties, which has given rise to a mushrooming near parasitical consultancy industry aimed at managing and reducing risk and charging for the pleasure.

One aspect that has perhaps received less attention, however, is the extent to which EU data protection rules might affect disclosure of documents in arbitration and to much lesser extent the impact of GDPR on the practice of adjudicators and adjudication proceedings. This audience knows there is no ‘disclosure’ in HGCRA/LDEDCA adjudication as we know it in court or arbitration. But the recentMr Jonathan Acton Davis QC decision in Vinci Construction UK Ltd v Beumer Group UK Ltd[2018]12 may change that position ever so slightly.

The judge in Beumer found that the adjudicator did not order disclosure because he was not requested to do so and that nothing was put before him that would have required him to make such an order. But one can see where this may be heading, particularly under TeCSA Sub-rule 18.2 and 18.3.

“18.2 Require any Party to produce a bundle of key documents, whether helpful or otherwise to that Party's case, and to draw such inference as may seem proper from any imbalance in such bundle that may become apparent…

18.3 Require the delivery to him and/or the other Parties of copies of any documents other than documents that would be privileged from production to a court…”

What we do with personal data

The definition of “personal data” for the purposes of EU law is very broad. It is broader than under US law and certainly broad enough to catch some of the documents that would routinely be disclosed in litigation or arbitration.

For example, email negotiations carried out by an employee of a company with a third party might well constitute the “personal data” of that employee or third party and, therefore, subject to the constraints imposed by the GDPR. Similarly, the broad definition of “processing” under EU law would certainly encompass the application of a litigation hold and all aspects of the performance of disclosure.

This means that the performance of disclosure/discovery obligations in litigation or arbitration may be, prima facie, inconsistent with EU law data protection constraints on the processing and transfer of data. What is to happen if a party to litigation is ordered to disclose documents that are subject to data protection constraints? In the context of English court litigation, any contradiction is addressed by the provision in the GDPR recognising that processing of data is lawful where it is necessary to comply with a legal obligation, including a court order to disclose documents.

However, no such legal obligation arises from arbitration, or adjudication which in the case of arbitration is consensual and in which the arbitrator’s directions give rise to contractual, or perhaps quasi-contractual, obligations. In Adjudication it is statutory and contractual express or statutorily implied.

This has led commentators to argue that disclosure obligations in arbitral proceedings may fall within a further ground of lawfulness provided for in the GDPR: that the processing is necessary for the purposes of legitimate interests13 pursued by the data controller. The same might be said of adjudication. However, this is a much more fluid and nebulous ground, and may be displaced where the interests of the individual data subject outweigh those legitimate interests. Furthermore, the general scheme of the GDPR is to require processing to be limited to that which is proportionate and necessary to achieve the stated purpose. This introduces a still further level of nuance and fluidity in arbitration. It suggests, for example, that it may no longer be acceptable to search for, collate, and disclose all “relevant” documents. Instead, considerations of proportionality may point towards a more focused process of identification, assessment and weighing, in order to ensure that data protection obligations are not breached. The lack of a formal disclosure process in adjudication makes it far less relevant to worry about as processing will generally limited.

What may be more relevant is what you as an adjudicator do with data you process if it concerns the processing of ‘personal data’, which is we have seen is defined as ‘any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person’.

An identifiable natural person is defined as a person ‘who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name,

- an identification number,

- location data,

- an online identifier

- or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person’.

For example as a lawyer the GDPR requires me to tell the data subject who I am, how that person can contact me about their personal data, for what purposes I may process their personal data and the legal basis for doing so, the people with whom I may share their personal data, the circumstances in which I may transfer their personal data outside the UK and/or the EU, the period for which I will store their personal data and the criteria I use for deciding how long to retain this personal data of theirs. The GPDR also requires me to tell the person how they can request access to and rectification or erasure of their personal data, how to make a complaint etc.

As a contractor mostconstruction companies will generally engage employees who perhaps operate a form of security/access control to their sites (especially if these use biometric access control measures) so they need to ensure that the obligations contained within GDPR are complied with. As a result, those companies may need to consider:

- carrying out an audit of the personal data that they use or hold in their business, why they hold it, how long they hold it for, who they share that personal data with, where they store that personal data in order to better understand their exposure to the GDPR;

- reviewing their existing processes to determine whether they are GDPR compliant

- training teams on what they should be doing in light of GDPR and what they should be doing if they receive any requests from individuals in relation to their personal data, as well as any other requests for access to personal data; and

- updating internal business policies if they are not GDPR compliant

Who am I?

I am Simon Tolson, a solicitor practising from Fenwick Elliott LLP in the Aldwych, in London. I am the ‘controller’ of your personal data for the purposes of the GDPR and the UK Data Protection Act 2018.

If you need to contact me about your personal data or a privacy notice, if you have any questions or complaints about our Privacy Notice or the way your personal information is processed by us, or would like to exercise one of your rights set out above, please contact us by one of the following means:

Email:

nelliot@fenwickelliott.com [1]

Post:

Fenwick Elliott LLP…

Categories of personal data that I may process about you

The most common category of personal data that I may process about you is your name and contact details, including where you currently work and (in some instances) your previous places of work.

Other categories of personal data that I may hold and process about you include, for example, your professional qualifications, dates and places of employment, details of your salary and related benefits (where that information was provided in the context of legal proceedings) or your religion (where provided in the context of you giving sworn

In addition to the categories outlined above, I may also process other categories of data that you or others have provided to me, or that I have obtained from publicly available sources in the course of legal proceedings and/or my legal practice.

How I may use your personal data

I may use your personal data for the following purposes:

- to provide legal services to my clients, including the provision of legal advice and representation in courts, tribunals, adjudications, dispute boards, arbitrations, settlement negotiations and mediations, or when acting as an arbitrator, adjudicator, mediator or dispute board member;

- to keep accounting records and carry out administration of my practice;

- to take or defend legal or regulatory proceedings or to exercise a lien;

- to respond to potential complaints or make complaints;

- to check for potential conflicts of interest in relation to future potential cases;

- to promote and market my/firm services;

- to carry out anti-money laundering and terrorist financing checks;

- to train other solicitors and when providing work-shadowing opportunities;

- to respond to requests for references;

- when procuring goods and services;

- to publish legal judgments and decisions of courts and tribunals; and

- as required or permitted by law.

When you have to provide me with your personal data

If I have been instructed by you or on your behalf on a case or if you have asked for a reference, your personal data has to be provided, to enable me to provide you with advice or representation or the reference, and to enable me to comply with my professional obligations, and to keep accounting records. If you refuse to provide personal data in situations where I am required to obtain this data by law or my professional obligations, I may have to refuse your instructions.

The legal bases for processing your personal data

I rely on the following as legal bases for processing your personal data:

i. If you have consented to the processing of your personal data for specific purposes, then I may process your data for those purposes.

ii. If you are a client, processing your personal data is necessary for the performance of a contract for legal services or in order to take steps at your request prior to entering into a contract.

iii. For categories of personal data that are deemed to be ‘sensitive’ under the GPDR and related legislation, I process your data only to the extent that you have expressly consented, or to the extent that I am entitled by law to process the data where the processing is necessary for legal proceedings, legal advice, or otherwise for establishing, exercising or defending legal rights.

iv. In relation to categories of personal data that are not deemed to be ‘sensitive’, I rely on my legitimate interests when processing your personal data. These legitimate interests include but are not limited to:

- Contacting you in relation to specific legal proceedings or for marketing purposes;

- Providing legal services to my clients, including the provision of legal advice and

- representation in courts, tribunals, adjudications, dispute boards, arbitrations, settlement negotiations and mediations, or when acting as an arbitrator, mediator, adjudicator or dispute board member;

- Keeping accounting records and carrying out administration of my practice;

- Taking or defending legal or regulatory proceedings or to exercise a lien;

- Responding to potential complaints or make complaints;

- Checking for potential conflicts of interest in relation to future potential cases;

- Carrying out anti-money laundering and terrorist financing checks;

- Training other part qualified solicitors and when providing work-shadowing opportunities;

- Responding to requests for references;

- Procuring goods and services; and

- Publishing legal judgments and decisions of courts and tribunals.

In certain circumstances processing may be necessary in order that I can comply with a legal obligation to which I am subject in the UK or elsewhere (including carrying out anti-money laundering or terrorist financing checks).

Who will I share your personal data with?

If I am not sitting as arbitrator or adjudicator. Well if you are my client, some of the personal data you provide will be protected by legal professional privilege14 unless and until the information becomes public. As a solicitor I have an obligation to keep your personal data confidential, except where it otherwise becomes public or is disclosed as part of the case or proceedings.

It may be necessary to share your information with the following:

- Data processors, such as my staff, IT support staff, email providers, data storage providers, my personal assistant, my personal administrator and accountant;

- Other legal professionals, including trainees assisting me on a matter;

- Experts and other witnesses;

- Prosecution authorities in the UK or otherwise;

- Courts and tribunals;

- In the event of complaints, my Partners/Members and staff who deal with complaints, the SRA, and the Legal Ombudsman,

- Other regulatory authorities,

- Business associates, professional advisers and trade bodies, e.g. the Law Society and SRA.

- The intended recipient, where you have asked me to provide a reference, and

- The general public in relation to the publication of legal judgments and decisions of courts and tribunals.

Have mobility, will travel, thus there will be transfer of your information outside the European Economic Area (EEA)

Here I may say the nature of our/my practice is that I travel extensively including outside the EEA. As such, while I endeavour to keep minimal non-public personal data on my laptop or mobile phone, if your personal data is held on my laptop or mobile phone or in hard copy, your personal data will be transferred outside of the EEA. I take all reasonable measures (including encryption of my laptop and mobile phone) to protect your data.

If you are in a country outside the EEA or if the instructions you provide come from outside the EEA then it is inevitable that information will be transferred to those countries.

Some countries and organisations outside the EEA have been assessed by the European Commission and their data protection laws and procedures found to show adequate protection. The list can be found here [2]. Most do not. If your information has to be transferred outside the EEA, then it may not have the same protections and you may not have the same rights as you would within the EEA.

I may be required to provide your personal data to regulators, such as the Law Society and SRA, the Financial Conduct Authority or the Information Commissioner’s Office. In the case of the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), there is a risk that your personal data may lawfully be disclosed by them for the purpose of any other civil or criminal proceedings, without my consent or yours, which includes privileged information.

The rights of data subjects

The rights of data subjects is one of the central areas in the GDPR.

The right for individuals to have access to personal data which is held about them is one of these rights. The ability of individuals to exercise these rights to obtain copies of their personal data (often referred to as making a data subject access request (“DSAR”) verbally or in writing15)is something which may be either a help or a hindrance to proceedings depending on who you are acting for.

Note - DSAR’s lean towards supporting the data subject who is doing the asking!

Note:

- Fees: Organisations will no longer be able to charge the previous £10 fee, which (though minimal) did act as a limited deterrent.

- Unfounded or excessive requests: Where a DSAR is “manifestly unfounded or excessive”, the organisation can charge a fee or refuse to respond. The burden is on the organisation to show that the DSAR was manifestly unfounded or excessive in character.

- Time limit for response: An organisation must respond to a DSAR without undue delay and, in any event, within one month of receipt. This is shorter than the current 40-day period that UK organisations have been used to. The one-month period can be extended to three months, taking into account the complexity and number of DSARs, in which case the data subject must beinformed of the extension (including reasons) within one month of receipt of the DSAR.

- Content of response: As well as access to the data subject’s personal data, the right of access extends to other information, including: the envisaged storage period for the personal data; the right to request rectification, erasure or restriction of processing; the right to lodge a complaint with the Data Protection Authority; and, if automated decision-making is used, meaningful information on the logic involved.

BUT: Where the data subject has previously provided consent to say a lawyer processing your personal data, you have the right to withdraw this consent at any time, but this will not affect the lawfulness of any processing activity the lawyer carried out prior to you withdrawing your consent. However, where a lawyer also relies on other bases for processing your information, you may not be able to prevent processing of your data.

But when I say lawyer, that does not apply necessarily to a lawyer acting as adjudicator or arbitrator where LPP may not apply and they are not legal advisers with clients.

- Electronic DSARs: It must be possible to make DSARs electronically and, unless otherwise requested by the data subject, the organisation must provide the information in a commonly used electronic form.

Note ‘special category data’, personaldata may, for example, relate to employees, customers or business contacts. Sensitive data (or “special category data”) needs to be handled with even greater care than mere personal data but is probably less likely to be present in standard commercial disputes. Sensitive data includes data revealing racial or ethnic origin or political opinions, or data concerning health, but does not include financial information (e.g. bank account or credit card numbers).

As a solicitor for example it is possible that I may need to provide advice to my clients, or indeed take a view myself in response to a request I have received, as to whether personal data can be withheld on the basis of legal professional privilege or confidentiality. Under the Data Protection Act 2018 exemptions apply to:

- information in respect of which a claim of legal professional privilege could be maintained in legal proceedings, or

- information in respect of which a duty of confidentiality is owed as a professional legal adviser.

For disclosure in English civil litigation, the main risk, from a data protection perspective, is probably disclosing “irrelevant” or “non-responsive” personal data. That is, personal data that is not clearly caught by the disclosure regime ordered by the court.

This risk can be mitigated by redaction in the same way that “irrelevant” confidential data may be redacted, although this is both difficult and costly. In particular, the definition of personal data means that redacting someone’s name is unlikely, of itself, to be sufficient to remove all personal data from any given document.

It is highly likely that the individual can still be identified from other data and/or the context. Redaction has a place, but it is neither a wholesale solution nor required in every instance.

What about compensation claims?

The GDPR sets out a right for individuals to seek compensation for either material or non-material loss which they suffer as a result of infringements by either controllers or processors. This is, of course, not a new concept. It was possible for individuals to raise claims under the Data Protection Act 1998. A recent example of this was the December 2017 decision in the case of Various Claimants v Wm Morrisons Supermarket PLC [2017] EWHC 3113 where 5,518 employees claimed compensation from Morrisons on the basis of the actions of an employee who has posted personal data of around 100,000 of Morrisons employees on the internet.

Whilst it may often difficult for individuals to claim a large amount of compensation for a personal data breach, group actions where a breach has affected a large number of individuals such as the Morrisons case may prove very costly.

It will be impossible for anyone here to have avoided hearing about the General Data Protection Regulation (the GDPR) which came into force on Friday 25 May, especially given the large numbers of emails circulated in advance by organisations wanting to make sure they could still keep in touch!

Parts of the Data Protection Act 2018 also came in force on 25 May. This was grease lightening when you consider that the text of it was only finalised on 21 May and royal assent was only granted on 23 May 2018.

Personal data will generally require to be shared a number of times before, during and after the course of dispute. Examples of this include running traces to obtain up to date contact details for an opposing party, instructing claims consultants and lawyers to prepare papers, sending papers to court for issue etc.

Considering the role of the person with whom personal data will be shared is important as different procedures will need to be applied depending on whether they are classified as a processor or controller. Making sure that appropriate procedures are followed and being clear what will happen to persona data when you share it is important.

Most lawful bases require that processing is ‘necessary’. If you can reasonably achieve the same purpose without the processing, you won’t have a lawful basis.

You must determine your lawful basis before you begin processing, and you should document it.

Take care to get it right first time - you should not swap to a different lawful basis at a later date without good reason. In particular, you cannot usually swap from consent to a different basis.

You must have a valid lawful basis in order to process personal data.

There are six available lawful bases for processing. No single basis is ’better’ or more important than the others – which basis is most appropriate to use will depend on your purpose and relationship with the individual.

Almost any interaction with personal data will amount to processing, including collecting, organising, storing, altering, retrieving, using, and erasing.

Personal data encompasses any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (expressly including a name, online identifiers (eg IP addresses) and genetic identity).

Laptops on trains, sending emails to wrong recipient, sloppy passwords and divulging16, 72 hours report breach to information commissioner.

- a duty on all organisations to report certain types of personal data breach to the relevant supervisory authority. You must do this within 72 hours of becoming aware of the breach, where feasible.

- If the breach is likely to result in a high risk of adversely affecting individuals’ rights and freedoms, you must also inform those individuals without undue delay.

- You should ensure you have robust breach detection, investigation and internal reporting procedures in place. This will facilitate decision-making about whether or not you need to notify the relevant supervisory authority and the affected individuals.

- You must also keep a record of any personal data breaches, regardless of whether you are required to notify.

Personal data is therefore not limited only to the identifiers themselves, but also includes almost anything linked to those identifiers. A data controller is the entity which, alone or jointly, determines the purposes and means of processing, and both the client and its lawyer will usually be data controllers.

External lawyers will typically be data controllers: they have their own professional responsibilities (in terms of record keeping, the confidentiality of communications, etc.) and exercise a degree of autonomy (e.g. in determining what information to request from their client and what to process in order to provide legal advice).

The concept of personal data has always been drawn extremely widely under EU data protection laws and this remains the case under the GDPR.

The EU General Data Protection Regulation (universally known as GDPR) has become ubiquitous. Less understood is what GDPR means for disputes and contentious regulatory/enforcement matters. Virtually all evidence, whether in arbitration or litigation relating to investigations carried out by regulators or enforcement authorities, will contain personal data.

‘Disclosure’ comes in many shapes and sizes. It has nearly as many names: discovery, disclosure, production of documents, inspection and so on. It encompasses not only the specific meaning in English civil litigation under the Civil Procedure Rules, but also whenever documents are collected, reviewed or produced in a legal, (regulatory or enforcement) context. This may be under compulsion or due to a desire to share those documents with another party.

- to the extent the risks exist, they are most acute, when data is being transferred from within the European Economic Area (EEA) to a jurisdiction outside the EEA (most often to the US).

- So-called “e-disclosure” is unlikely to change. The Article 29 Data Protection Working Party (WP29) has not provided any further words of wisdom concerning the difficulties posed by data flows in and (especially) out of the EU in the context of litigation being conducted in common law countries. Litigators will continue to struggle with the conflicts between common law pre-trial discovery and the civil code countries.

- dispute resolution lawyers will have to ensure that not only is their own house in order, but also that of any providers that they engage with in respect of client data. I am thinking in terms of how data is managed, stored, accessed and protected, both whilst it is in use, and after the tasks for which it was collected have been completed. A prudent lawyer and his or her firm will already have stringent processesand procedures in place to look after and work with client data, so they will be less impacted by the changes. Their new focus will be to take responsibility for ensuring that any provider they use to work with the data also has adequate protection processes in place.

- As lawyers for example we must have data protection in mind at all times so that decisions one takes factor it in. For example, in disclosure under the Civil Procedure Rules (CPR) this means: when the client initially gathers documents, whenever a third party is used to assist with the disclosure process, whenever disclosure documents are being transferred, whenever the documents are reviewed, whether it is appropriate to redact documents, right up to decisions about for how long and in what circumstances lawyers should retain documents after a dispute has been resolved.

Erasure

One of the most (in)famous aspects of the GDPR is the Right to Erasure, (aka The Right to be Forgotten). But it’s not quite as simple as it first appears.

Article 17 of the GDPR states that data subjects have the right to have their personal data removed from the systems of controllers and processors under a number of circumstances, such as by removing their consent for its processing. It’s akin to requesting your neighbour return the lawnmower you lent them. It’s yours, and you want it back.

On the face of it, complying with this is a daunting task, and to add to the complexity, there are many cases where conflicting regulations will prevent the processor from complying with the request.

The Requirements

Article 17 of the GDPR, The Right To Erasure, states:

Data Subjects have the right to obtain erasure from the data controller, without undue delay, if one of the following applies:

- The controller doesn’t need the data anymore

- The subject withdraws consent for the processing with which they previously agreed to (and the controller doesn’t need to legally keep it [NB. Many will, e.g. banks, for 7 years, solicitors 12 years plus in some cases.])

- The subject uses their right to object (Article 21) to the data processing

- The controller and/or its processor is processing the data unlawfully

- There is a legal requirement for the data to be erased

- The data subject was a child at the time of collection (See Article 8 for more details on a child’s ability to consent)

If a controller makes the data public, then they are obligated to take reasonable steps to get other processors to erase the data, e.g. A website publishes an untrue story on an individual, and later is required to erase it, and also must request other websites erase their copy of the story.

Exceptions

Data might not have to be erased if any of the following apply:

- The “right of freedom and expression”

- The need to adhere to legal compliance, e.g. a bank keeping data for 7 years.

- Reasons of public interest in the area of public health

- Scientific, historical research or public interest archiving purposes

- For supporting legal claims, e.g. PPI offerings.

Out of Scope

Non-electronic documents which are not (to be) filed, (i.e. it’s data you can’t search for), e.g. a random piece of microfiche, or a paper notepad, are not classed as personal data in the GDPR and are therefore not subject to the right to erasure.

Not Going to Happen

Some personal data sets are impossible (or infeasible) to edit to remove individual records, e.g. a server backup or a piece of microfiche. Whilst these uneditable data sets are in-scope of the erasure Right, themselves they would be out-of-scope for erasure editing procedures due to their immutable nature. If you can destroy the whole microfiche and not worry about losing other data then great. It’s the “editing” of microfiche that wouldn’t be possible here.

The Real World

Once an organisation understands where all a subject’s personal data resides, an assessment must be made of what can be, should be, can’t be, and is infeasible to be erased. The exceptions above will commonly apply, such as legal requirements for data retention. But this doesn’t mean that the controller should keep the records “live” in an online system. To best protect the personal data it ideally should be archived away to a more protected and locked down system that meets the retention requirements and also goes as far as possible at meeting the data subject’s desire to be erased.

Importantly, these exceptions can’t be used as an override, e.g. allowing the controller to keep considering the subject as an active customer that they can keep marketing to. The Principles of GDPR should keep the controller focused on best serving the rights of the data subject as much as possible, whilst meeting their wider requirements.

My Advice on erasure

Erasure is an area where there is no black and white on what must be done. Every organisation, every record and every piece of technology used will require a case by case assessment. For example, some processors provide more granular control of deletion of individual records in cold backups. Some provide none.

The key is to focus on what your rationale would be if you were stood in front of the regulator (e.g. ICO in the UK) or a judge in court. Would you be confident that you had a justifiable position on doing the “right thing” by the data subjects, doing the best you could and had given this enough focus and documented thought? Focus on answering this question and you should be in a solid position.

Legal professional privilege

Under paragraph 19 of Part 4 of Schedule 2 to the DPA, subject access rights do not apply to:

...personal data that consists of information in respect of which a claim to legal professional privilege... could be maintained in legal proceedings.

Leaving aside the difficulties in applying to information a legal principle which has been developed in relation to documents, a solicitor's file will typically contain much unprivileged information. In Ittihadieh v 5-11 Cheyne Gardens RTM Co Ltd [2018] QB 256, at [102], Lewison LJ said:

If some personal data are covered by legal professional privilege and others are not, the data controller will have to carry out a proportionate search to separate the two.

The firm's obligation of confidentiality

Mere confidentiality is not a complete bar to a subject access request, but the right to access (of X) is qualified if the data is also the personal data of a third party (Y). Under paragraph 16 of Part 3 of Schedule 2 to the DPB, the subject data access provisions:

(1) ... do not oblige a controller to disclose information to the data subject (X) to the extent that doing so would involve disclosing information relating to another individual (Y) who can be identified from the information.

(2) Sub-paragraph (1) does not remove the controller's obligation where—

(a) the other individual (Y) has consented to the disclosure of the information to the data subject (X), or

(b) it is reasonable to disclose the information to the data subject (X) without the consent of the other individual (Y).

(3) In determining whether it is reasonable to disclose the information without consent, the controller must have regard to all the relevant circumstances, including—

(a) the type of information that would be disclosed,

(b) any duty of confidentiality owed to the other individual (Y)...

This exemption (which does not appear to have been directly in issue before the Court of Appeal in either Dawson-Damer or Ittihadieh) is naturally likely to have a more pervasive effect when the solicitor's client (Y) is an individual, rather than a corporation. In Ittihadieh, at [101], Lewison LJ observed that:

...whether it is reasonable to disclose information about another individual (Y) is an evaluative judgment which must, as it seems to me in the current state of technology, be carried out by a human being rather than by a computer.

Collateral purpose

The Court of Appeal in both Dawson-Damer (at [105] to [114]) and Ittihadieh (at [86] to [89]) rejected the submission that a subject access request was invalid if it was made with a collateral purpose, such as litigation.

Disproportionality

The judgments in Dawson-Damer and Ittihadieh are not encouraging for solicitors seeking to reject a subject access request outright on the basis that it is disproportionate, but they both confirm that principles of proportionality apply implicitly to the burdens of search, analysis and production which are imposed by a request (Dawson-Damer, at [74] to [79]; Ittihadieh, at [95] to [103]).

In Gaines-Cooper v Commissioners for HMRC [2017] EWHC 868 (Ch) HHJ Jarman QC held that HMRC, which had made significant efforts to comply with a subject access request, had done enough to comply with its obligations, even though significant quantities of potentially relevant documentation remained unexamined.

Abuse of process/abuse of rights

In Dawson-Damer, at [109], the Court of Appeal raised the possibility that an application to enforce rights of access might in some circumstances amount to an abuse of process, and this possibility was confirmed in Ittadieh, at [88]. The Court of Appeal suggested in the latter case that there was not much difference between the domestic concept of abuse of process and the EU doctrine of "abuse of rights".

The Court's discretion

In Ittihadieh, at [104] to [110], the Court of Appeal considered the nature of the Court's discretion on applications by data subjects to enforce their access rights. It held that if a data controller had failed to conduct a proportionate search in response to a valid request then, absent other material factors, the Court's discretion should usually be exercised in favour of the data subject.

However, the Court of Appeal also identified a number of factors which are of potential relevance to the Court's exercise of its discretion, including:

- whether there is a more appropriate route to obtaining the requested information

- the nature and gravity of the data controller's breach

- whether there is a legitimate reason for making the access request

- whether an abuse of rights is involved

- whether the application is procedurally abusive

- whether the real quest is for documents, rather than personal data

- whether the personal data is of no real value to the data subject

- whether the data subject has already received the data

The Court of Appeal stated that this list was not intended to be prescriptive, but it is likely to be the subject of close examination on many future applications.

One suspects that (as may already be detected in the existing case-law) the courts' application of the relevant principles will be significantly influenced by their perception of the virtues or demerits of the individual litigants involved.

Conclusion.

Following the implementation of the GDPR, subject access requests of solicitors are likely to become more common. The requests can raise a whole host of difficult issues, which can be time-consuming and costly to resolve (and not billable). Further, the proper response to the requests is often counter-intuitive.

On the other side of the coin, solicitors and the claims community advising individuals in relation to potential or current proceedings should consider whether or not to advise their client to make a subject access request. Such a request may succeed in eliciting sought after information or documentation, where an application for pre-action or third-party disclosure would fail.

I leave with a joke. There is a joke circulating on the Internet, based on the classic song, “Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town”.

He's making a list.

He's checking it twice.

He's gonna find out who's naughty or nice.

Santa Claus is in contravention of Article 4 of the General Data Protection Regulation.

Ah yes - the cruelty of GDPR – Christmas is cancelled!

Now some common sense please.

19 October 2018

Simon Tolson

Fenwick Elliott LLP

- 1. Noble Design and Build of Telford, Shropshire, which operates CCTV systems in buildings across Sheffield, broke data protection laws by failing to comply with an Information Notice.

The company also failed to register with the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), despite it being a criminal offence to do so.

On Monday 2 July 2018, the company was convicted at Telford Magistrates’ Court, in their absence. They were fined £2000 for failing to comply with an Information Notice, under section 47 of the Data Protection Act 1998.

They were also fined £2500 for processing personal data electronically without having notified when required to do so, under Section 17 of the Data Protection Act 1998, and ordered to pay costs of £364.08 and a victim surcharge of £170.00.

On 4 September 2017, the ICO sent a letter to Noble Design and Build, raising concerns that it didn’t have the appropriate signage in place to alert people to the CCTV. It also notified the firm of its legal duty to register with the ICO. - 2. GDPR Articles 4(1), Recital 30

- 3. GDPR Articles 4(8)

- 4. GDPR Articles 4(7)

- 5. They a "natural individuals".

- 6. Section 170 of the DPA18 builds on s.55 DPA 1998 which criminalised knowingly or recklessly obtaining, disclosing or procuring personal data without the consent of the data controller, and the sale or offering for sale of that data. The provision was most typically/ used to prosecute those who had accessed healthcare and financial records without a legitimate reason. This adds the offence of knowingly or recklessly retaining personal data (which may have been lawfully obtained) without the consent of the data controller.

Section 184 relates to Subject Access Requests and builds on s.56 DPA 1998. It is designed to prevent organisations from trying to use Subject Access Requests as background checks. It creates the offence of requiring relevant records (a record relating to health, convictions or cautions, or statutory functions), as a requirement for employment or a contract for the provision of services. Organisations are expected to run the necessary background checks without compelling people to obtain and disclose their personal data.

The Act empowers prosecutors to proceed against individuals, body corporates and those associated with them. Directors are put in the spotlight as Section 198 (which is intended to have the same effect as s.61 DPA 1998), provides that where an offence has been committed by a body corporate with the consent or connivance of an officer (or a person purporting to act in that capacity) then both the body corporate and the relevant person are liable to prosecution - 7. Special category data is more sensitive, and so needs more protection. For example, information about an individual’s: race; ethnic origin; politics; religion; trade union membership; genetics; biometrics (where used for ID purposes); health; sex life; or sexual orientation.

- 8.

- 9. The term “third country” refers to those countries that are not members of the EU. Should the currently planned withdrawal date remain as agreed, transfers of data with companies based in the UK cannot legally be treated the same as data transfers with companies based in Germany or other EU member states as from 30 March 2019, 00.00h (CET). Thus, the transfer of data to the United Kingdom will need to be treated in a similar way to the transfer of data to the United States. Such transfers of data will require further arrangements in order to be legally legitimised.

- 10. The GDPR is aimed at organisations processing personal data either as controllers (i.e. those with the interest in processing the data) or as those processing on behalf of controllers (i.e. data processors). Whilst the definition of “personal data” under the GDPR is not fundamentally different from that under the Directive, it expressly expands the scope of the law to “online identifiers” and “location data”.

- 11. Which involved the collection of personally identifiable information of 87 million Facebook users and reportedly a much greater number more that Cambridge Analytica began collecting in 2014.

- 12. EWHC 1874

- 13. Legitimate interests is the most flexible lawful basis for processing, but you cannot assume it will always be the most appropriate.

It is likely to be most appropriate where you use people’s data in ways they would reasonably expect and which have a minimal privacy impact, or where there is a compelling justification for the processing.

If you choose to rely on legitimate interests, you are taking on extra responsibility for considering and protecting people’s rights and interests.

The processing must be necessary. If you can reasonably achieve the same result in another less intrusive way, legitimate interests will not apply. - 14. This exemption pursuant to Article 23 and (Schedule 2 para 19) of DPA18 applies and if you process personal data: to which a claim to legal professional privilege could be maintained in legal proceedings; or in respect of which a duty of confidentiality is owed by a professional legal adviser to his client. It exempts a solicitor or barrister from the GDPR’s provisions on: the right to be informed; the right of access; and all the principles.

- 15. You have one month to respond to a request. You cannot charge a fee to deal with a request in most circumstances. Individuals have the right to obtain the following from you: confirmation that you are processing their personal data; a copy of their personal data; and other supplementary information – this largely corresponds to the information that you should provide in a privacy notice (see ‘Supplementary information’ below).

- 16. A personal data breach means a breach of security leading to the accidental or unlawful destruction, loss, alteration, unauthorised disclosure of, or access to, personal data. This includes breaches that are the result of both accidental and deliberate causes. It also means that a breach is more than just about losing personal data.