February 2017

A Yellow Book Tale: Termination, Letters of Credit and a Question of Fraud

In this Insight, we look at a recent Court of Appeal case on On-Demand Performance Securities (specifically Standby Letters of Credit) provided by a Brazilian contractor (“Construtora” or “OAS”) to the National Infrastructure Development Company (“NIDCO”) pursuant to a FIDIC Yellow Book contract. Fenwick Elliott1 acted for the successful party, NIDCO, against Santander in a claim for circa US$38 million.

NIDCO v BNP Paribas; NIDCO v Santander: the First Round2

NIDCO v Santander, like Petrosaudi,3 reaffirms the autonomy principle for On-Demand Performance Securities and the narrow scope of the fraud exception to that principle. If the party making the demand on the security honestly believed it was entitled to make the demand, fraud will not be made out, even if that party’s belief proves to be wrong. It also provides some comfort to FIDIC users that the system of securities in place for contractual terminations (even if disputed) is sound.

In NIDCO v Santander the Court of Appeal also clarifies the law as to the proper test to be applied on summary judgment applications by beneficiaries under letters of credit. There must be a “real prospect” of establishing “that the only realistic inference is that [the claimant] could not honestly have believed in the validity of the demands”. This test will also apply where the beneficiary of an On-Demand Bond wishes to force the bank or other entity that issued it to pay out (to be contrasted with a Contractor seeking to injunct a bank from paying out to an Employer).

However, before seeking to distil the lessons learnt from the Court of Appeal, it is perhaps worth recapping on NIDCO’s claims for payment against both BNP Paribas and Santander at first instance.

Santander was one of a number of banks that had provided securities (retention, advance payment and performance securities) at the request of a Brazilian contractor (Construtora) pursuant to a FIDIC Yellow Book contract (with bespoke amendments) for the construction of a major highway project in Trinidad and Tobago. The Employer for the contract was NIDCO, a corporate vehicle used by the government of Trinidad and Tobago to effect public infrastructure works.

The securities under the contract were all issued in the form of Standby Letters of Credit. They were also subject to English law and the jurisdiction of the English courts.

Standby Letters of Credit and the Autonomy Principle

For those wondering, Standby Letters of Credit are a special form of letter of credit frequently used in international trade contracts. They originate from the US where prohibitions were imposed on national banking associations from issuing bonds by way of guarantees as “payment of last resort”. As with both traditional letters of credit and bonds the bank gives an undertaking to pay against documents, which creates a primary obligation on the bank that is autonomous of the underlying transaction.4 Letter of credit transactions are, by their nature, international and have retained their role as an instrumentality for the financing of foreign trade.

As such, Standby Letters of Credit are subject to the autonomy principle (as are On- Demand Performance Securities more generally under English law). Basically, if the demand made complies with the terms for making a demand on its face, then the monies claimed must be paid. The only exception under English law (as opposed to other jurisdictions such as Singapore and Australia where a doctrine of “unconscionability” has developed) is fraud.

Lord Denning famously explained this in Edward Owen Engineering Ltd v Barclays Bank International:5

“A bank which gives a performance guarantee must honour that performance guarantee according to its terms. It is not concerned in the least with the relations between the supplier and the customer; nor with the question whether the supplier has performed his contractual obligations or not; nor with the question whether the supplier is in default or not. The bank must pay according to its guarantee, on demand, if so stipulated without proof or conditions. The only exception is when there is a clear fraud of which the bank has notice.” [Emphasis added]

The Dispute

So what happened in the NIDCO cases?

Significant disputes arose in respect of the construction contract resulting in a termination notice being served in June 2016. Construtora had, prior to that, gone into the Brazilian equivalent of Chapter 11 style administration. Following the termination, an LCIA arbitration was commenced which is ongoing. NIDCO also served various demands in respect of the Standby Letters of Credit (“LoCs”).

Aside from numerous LoCs issued by Citibank based in the US, the remainder of the LoCs had been provided by banks incorporated in Europe.

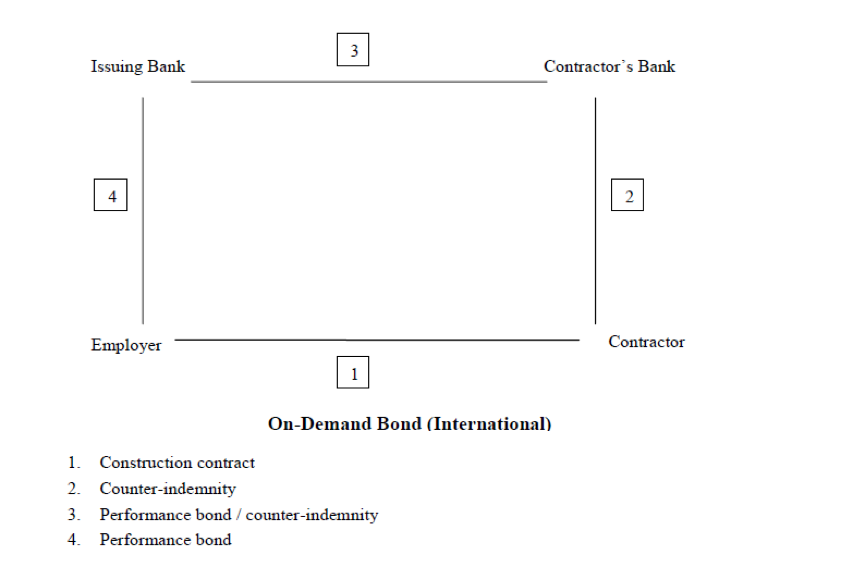

As is common in such transactions, the banks had taken counter-indemnities from their Brazilian subsidiaries. Typically these are then secured against monies or assets of the Contractor to ensure that the bank is not left out of pocket if a call is made on a security. The diagram below sets out the typical contractual relationships between the parties in the context of international on-demand performance securities.

The Brazilian subsidiaries of the European banks (who had provided counter-indemnities to their European counterparts) were injuncted by the Brazilian courts from paying out to NIDCO in the first half of July 2016. The Brazilian courts later extended their injunction to cover the European banks. Both banks declined to pay out the monies demanded by NIDCO, noting that a substantial fine would be payable if they did so.

NIDCO applied for summary judgment in the sum of approximately US$58 million against BNP Paribas and US$38 million against Santander. The BNP Paribas case came before the Commercial Court on 26 September 2016, with the Santander hearing following in November.

At the first hearing in September, the issue was whether the Brazilian injunction gave BNP Paribas any arguable defence or grounds for resisting payment under English law. The Judge6 emphasised that LoCs have a status which is the equivalent to cash and should be paid out unless the very limited exceptions applied. He noted:

“Whilst it is said that the facts of the present case are extraordinary, I suspect they would become commonplace if a party who had opened a letter of credit could defeat the bank’s payment obligation to pay by obtaining an injunction against the bank in its home jurisdiction.” [Emphasis added]

The Judge accordingly ordered summary judgment to be granted. He also refused permission for a stay, stating that it would be “wrong in principle to use a stay of execution to subvert the principles of substantive law which provide very limited defences indeed to claims to enforce letters of credit”.

BNP Paribas did not appeal the judgment, paying out shortly afterwards.

The next hearing was against Santander. To win, Santander had to distinguish its position from that of BNP Paribas. Relying on the Brazilian injunction to avoid payment clearly wasn’t going to work.

As a result, less reliance was placed on the Brazilian injunction in resisting the demand for payment. Instead Santander argued that the fraud exception applied to stop payment. This was primarily on the basis that the amounts said to be due by NIDCO had not yet been subject to a final determination (the arbitration had not yet determined what was “due and owing”). As such NIDCO could not, they said, have an honest belief in their demands. Further, it was argued that English law should be extended to include a doctrine of “unconscionability” as applicable in Singapore and some other jurisdictions. Santander argued that given the Brazilian injunction and NIDCO’s alleged financial status it would be unconscionable to order payment.

Santander’s arguments were rejected. Mr Justice Knowles noted the recent case of J Murphy and Sons v Beckton Energy Ltd7 in which Mrs Justice Carr held:

“The trigger for a performance bond is a belief on the part of the drawing party in its entitlement, not such entitlement having been subject to a final determination giving rise to a payment obligation.”

There was no seriously arguable case that NIDCO did not believe in the validity of the demands and, as such, payment had to be made. The Judge further noted that the parties had chosen English law to govern the LoCs which did not recognise a doctrine of unconscionability.

Santander sought permission to appeal and was granted it by the Court of Appeal on all grounds save one. This was, namely, that the attempt to bring the principle of unconscionability into English law was denied and, as a result, this issue was not reviewed by the Court of Appeal.

NIDCO v Santander: the Appeal

The six grounds on which Santander sought to appeal the first instance judgment were as follows:

- The judge applied an incorrect test of serious arguability when he should have asked himself whether the bank had a real prospect of establishing its defence.

- The bank did have a real prospect of establishing that NIDCO did not believe in the validity of its claim because a claim for unliquidated damage for premature abandonment of the construction contract was not in law a claim that money was “due and owing”.

- The factual evidence relied on by the bank demonstrated that NIDCO had no genuine belief that money was due and owing from OAS.

- On any view the claim under the retention letters of credit could only be in respect of the certified retention; at the time of the demand the certified retention was only US$31m and it was therefore wrong to claim an amount of US$34m in respect of the retention security.

- It was wrong to give summary judgment without offering the bank an opportunity to cross-examine NIDCO’s witnesses.

- The judge’s refusal to order a stay in light of the Brazilian injunction was wrong in principle.8

What was the correct test to be applied?

Lord Justice Longmore confirmed that the correct test to apply was that there must be a “real prospect” of establishing “that the only realistic inference is that [the claimant] could not honestly have believed in the validity of the demands”.9 The Judge at first instance had applied too high a test by using the phrase “seriously arguable” rather than the wording of the summary judgment provisions within the Civil Procedure Rules (CPR 24), “no real prospect of success”, i.e. some chance of success. The prospect must be real and not false, fanciful or imaginary.

That did not, however, in the end make any difference (or as Lord Justice Longmore put it, succeeding on that ground was “so far as it goes”) as the test was not satisfied in any event, as confirmed by the remainder of the judgment.

“Due and Owing” and the Fraud Exception

The remainder of Santander’s arguments were decisively dismissed. A stay was also refused.

In relation to the question as to whether monies could be said to be “due and owing”, the Court of Appeal rejected the attempt to argue that this would have to be crystallised by agreement or an award following a termination before a call could be made.

For regular users of FIDIC contracts, it is worth noting that the Judge would have held (if required to do so) that it was clearly intended that the calls on the securities could be made on termination of the contract. Sums “due and owing” would include sums to which a party was entitled on “any alleged contractual termination”. Otherwise, the purpose of the securities would be voided, given the date for expiry of the securities may have passed by the time any arbitral award was issued. Indeed, had there been any other finding the security provisions within the FIDIC contracts would have required an extensive review.

As to the allegation that there was no evidence presented that NIDCO had turned its mind to whether the monies were “due and owing” and that this recklessness could be interpreted as tantamount to fraud, this was given short shrift:

“No doubt lawyers can have a debate as to whether a current entitlement to claim damages for repudiation entitles one to say that the amount of such damages is due and owing…. But it borders on the absurd to say that the only realistic inference from the fact that businessman did not have (or may not have had) that debate is that they could not have believed in the validity of their demands.” [Emphasis added]

Parallels to the Petrosaudi case

The similarities of the NIDCO v Santander case to the Petrosaudi Court of Appeal case are perhaps strongest in relation to the Court of Appeal’s analysis of what was passing through the mind of the party calling the security when they signed the demand.

In the Petrosaudi case, their General Counsel (a Mr Buckland – solicitor) had signed the demands made pursuant to the various letters of credit. He had certified that PDVSA (controlled in Venezuela and known for its late payments) was "obligated to [POS]… to pay the amount demanded under the Drilling Contract”.

He was essentially found to be fraudulent because “on the view that he took of the legal position”, he thought the monies under the underlying contract were due. The Judge at first instance had held that any underlying liability arising from the invoices could not yet be enforced and PDVSA had no present obligation to pay. He went on to consider that Mr Buckland did not honestly hold the belief that the monies were due and that, accordingly, he was fraudulent in signing the demand.

Lord Justice Clarke (who also heard the NIDCO appeal), noted in his Court of Appeal judgment that “whilst there is only one true construction of an instrument such as the certificate, different legal minds may obviously take different views on such a question”.10

In the Petrosaudi appeal, the Court of Appeal agreed that the monies could be called in any event but they also expressed “some disquiet”11 at the finding that Mr Buckland was fraudulent when he had simply had a different view as to whether certain invoices were payable.

The argument raised by Santander, and the respondents in Petrosaudi, was arguably a way of extending the fraud exception to the autonomy principle. If the party resisting a call had a different contractual interpretation to the underlying contract as to whether amounts were due, then the conclusion could be made that a call was “fraudulent” either as a result of recklessness or as a result of reaching the “wrong” conclusion as to whether an amount was due.

This is, in the author’s view, clearly wrong and inconsistent with the whole “pay now argue later” philosophy behind on-demand performance securities. Indeed, if the Court of Appeal hadn’t reached the conclusions it did, it would no doubt have led to far more disputes and attempts to avoid calls on such securities in the future.

Conclusion

The NIDCO v BNP Paribas, NIDCO v Santander and Petrosaudi judgments all uphold the autonomy principle under English law. As Lord Justice Longmore emphasises:

“Letters of Credit are part of the lifeblood of commerce and must be honoured in the absence of fraud on the part of the beneficiary. The whole point of them is that beneficiaries should be paid without regard to the merits of any underlying dispute between the beneficiary and its contractor.”

Attempts to argue that the doctrine of unconscionability should be extended to English law and/or to open up the fraud exception to consider whether someone’s contractual interpretation may be right or wrong have been firmly dismissed. For those beneficiaries seeking to enforce payment the test is clear – there must be a “real prospect” of establishing “that the only realistic inference is that [the claimant] could not honestly have believed in the validity of the demands”.

Lord Denning can rest easy, as indeed can FIDIC.

Claire King12

20 February 2017

- 1. Simon Tolson and Claire King acted for NIDCO. Anneliese Day QC of Fountain Court and Hugh Saunders of 4 New Square acted as Counsel for the first instance and Court of Appeal hearings against Banco Santander. Ben Patten QC acted as Counsel for the first instance hearing against BNP Paribas.

- 2. See Simon Tolson and Claire King’s article on this in Building magazine dated 2 December 2016 for further details.

- 3. Petrosaudi Oil Services (Venezuela) Ltd v (1) Novo Banco S.A.; (2) PDVSA Servicios S.A.; (3) PDVSA Services BV [2017] EWCA Civ 9.

- 4. Ali Malek QC and David Quest, Jack: Documentary Credits, The law and practice of documentary credits including standby credits and demand guarantees, Tottel Publishing, Fourth Edition, 2009, chapter 12.13, page 341.

- 5. Edward Owen Engineering Ltd v Barclays Bank International [1978] 1 All ER 976 (CA).

- 6. Mr David Foxton QC.

- 7. [2016] EWHC 607 (TCC).

- 8. See paragraph 25 of Lord Justice Longmore’s judgment in National Infrastructure Development Company Limited v Banco Santander S.A. [2017] EWCA Civ 27.

- 9. See paragraph 27 of Lord Justice Longmore’s judgment.

- 10. See paragraph 88 of the Petrosaudi Court of Appeal judgment.

- 11. See paragraph 88 of the Petrosaudi Court of Appeal judgment.

- 12. With thanks to Simon Tolson for his comments and suggestions.