January 2024

Bonds and Guarantees: What to focus on in the current economic environment

By Claire King

In the current economic environment, it is more important than ever to ensure that your project’s securities are set up correctly, or, if you are the party offering those securities, know what you have given. If your project has started to go downhill and a call is becoming more likely, it is equally important to know what steps need to be taken into order to call on those securities and/or take steps to avoid the necessity of a call being made (if possible). Case law is littered with examples of calls that have gone wrong because the parties have misunderstood what they have to do to make a call and/or the applicable timescales.

In this Insight, we1 focus on some the basic issues parties forget when offering securities, or checking the securities they have been offered, as well as outlining some of the practical steps and checks parties should take if they are considering making, or resisting, a call.

The basics

Before focusing on the issues outlined above, a refresher on the basic differences between on demand bonds, guarantees and hybrid forms of securities is set out below. When reviewing any security, the first point to have in mind is always that terminology is confusing, and the labels given to securities are all too often wrong. As precedents are amended over the years, they frequently morph into something different to what they may have started off as. As such, it is always essential to look at the security in question as a whole and ignore titles.

What is an On Demand Bond?

Titles such as “Demand” Guarantees (which are not guarantees at all), Performance Guarantees, Performance Bonds and Standby Letters for Credit are all used for On Demand Bonds. At its most basic an On Demand Bond is one where the bank or financial institution who has provided it makes immediate payment upon presentation of a compliant demand. The Law of Guarantees defines On Demand Bonds as “an irrevocable undertaking to pay a specified sum to the beneficiary in the event of a breach of contract, rather than a promise to see to it that the Contract will be performed…”.2 In its purest form then, an On Demand Bond will require no enquiry into the underlying rights and obligations of the parties to the underlying construction contract before payment is made.

On Demand Bonds often serve various different purposes in the construction industry. These are summarised below for convenience.

|

Type of On Demand Bond |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Tender Bonds |

The aim of Tender Bonds is to give assurance to an employer that the Contractor is serious about a bid. In some jurisdictions, Tender Bonds are used widely or are compulsory under the governing law. Typically, a Tender Bond will allow a call if: o The contractor withdraws the tender without the employer’s consent; o The contractor is awarded the tender but doesn’t enter the construction contract; or o The contractor doesn’t provide a Performance Bond as required under the underlying construction contract. |

|

Advanced Payment Bonds (“APB”) |

An APB will allow an employer to call back money paid for plant or equipment in advance due to high cost or criticality. It protects the employer from funds being diverted to pay for other works. |

|

Retention Bonds |

These are given in lieu of retention. They are typically reduced at practical completion or released at the end of the defects liability period. |

|

Performance Bonds |

These are intended in to ensure performance is in accordance with the construction contract. They generally are required to cover percentages of the contract price. Generally, they are provided for a constant percentage until practical completion. They are likely to expire completely at the end of the defects liability period. |

|

Off-Site Material Bonds |

These provide protection for the employer where materials are not on site but have been paid for. Off-site Material Bonds also provide protection against insolvency as the monies spent on those materials can be recouped if title to the materials has not passed to the employer for some reason. |

Resisting a call on an On Demand Bond

There are two ways to resist a call on an On Demand Bond under English law. Both are difficult to make out. They are:

- Obtaining an injunction against the bank (or financial institution) that provided the On Demand Bond on the basis of the fraud exception; and

- Obtaining an injunction against the person seeking to make the call under the main construction contract.

In relation to the fraud exception, the key case is Edward Owen Engineering Ltd v Barclays Bank International Ltd3 although there has been extensive case law on the extent of the fraud exception since 1978. As Lord Denning famously stated:

“So long as the Libyan customers make an honest demand, the banks are bound to pay: and the banks will rarely, if ever, be in a position to know whether the demand is honest or not. At any rate they will not be able to prove it to be dishonest, so they will have to pay. All this leads to the conclusion that the performance guarantee stands on a similar footing to a letter of credit. A bank which gives a performance guarantee must honour that guarantee according to its terms. It is not concerned in the least with the relations between the supplier and the customer; nor with the question whether the supplier has performed his contracted obligation or not; nor with the question whether the supplier is in default or not. The bank must pay according to its guarantee, on demand, if so stipulated, without proof or conditions. The only exception is when there is a clear fraud of which the bank has notice”. [Emphasis added]

It is worth emphasising that the bank must know about the fraud at the time the call is made. As stated in Group Josi Re Co SA v Walbrook Insurance Co Ltd4:

“… It is nothing to the point that at the time of trial, the Beneficiary knows, and the Bank knows, that the documents presented under the letter of credit were not truthful in a material respect. It is the time of presentation that is critical”. [Emphasis added]

There is therefore a heavy burden on the bank seeking to resist payment or the party seeking to restrain the bank. How can you prove a bank knows of a fraud?

The only other option under English law is to seek to restrain the beneficiary itself from making a call on the basis that the person seeking to make the call has not complied with the applicable contractual mechanisms under the underlying construction contract before making that call. Again, the difficulty of obtaining such an injunction under English law should not be underestimated.

In Permasteelisa Japan KK v Bouyguesstroi and Bank Intesa SPA5 it was held that the person seeking the injunction must “positively establish” that the demand would not comply with the underlying contractual mechanism. Having a “seriously arguable” position was not enough and the injunction was refused. In contrast, in Simon Carves Ltd v Ensus UK Ltd6 a “strong case” for an injunction was held to be sufficient. It was noted that “there is no legal authority which permits the Beneficiary to make a call on the Bond when it is expressly disentitled to do so”. Further, Doosan Babcock Ltd v Comercializadora de Equipos Y Materiales Mabe Lda7 held that a “realistic prospect” of showing that the employer had wrongfully failed to issue a takeover certificate in breach of contract meant that the employer could not benefit from its own wrong by issuing a demand. More recently however, it was the Permasteelisa test that was reverted to. In MW High Tech Projects v Biffa Waste Services Ltd8 the court held that the party seeking the injunction had failed to positively establish that the demand would not comply with the contractual mechanism.

Defending a call by injuncting the beneficiary is not therefore an easy task. As The Law of Guarantees9 highlights:

“It seems unlikely that the ground for interference would be extended by an English Court any further than, at the very most, a clear case of total failure of consideration, illegality or failure to comply with the condition precedent. Any wider exception would be too likely to divert to the value of the Performance Bond as a commercial instrument, to find favour with the court”. [Emphasis added]

What is a guarantee?

So how does a guarantee differ from an On Demand Bond? In the case of Vossloh AG v Alpha Trains (UK) Ltd10, a guarantee was defined as follows:

“A contract of guarantee, in the true sense, is a contract whereby the surety (the Guarantor) promises the creditor to be responsible for the due performance by the principal of his existing or future obligations to the creditor if the principal fails to perform them or any of them”.

Guarantees are then secondary, not primary, obligations. Crucially, liability and the amount of that liability, needs to be established and ascertained before payment is made. The creditor must be a party to the guarantee (i.e., it is a tripartite contract) and its liability is the same as the creditor has pursuant to the underlying contract. A clause confirming that an amendment to the underlying contract will not relieve the Guarantor of their liability in a guarantee is also necessary to avoid the Guarantor being let of the hook if there is an amended to the underlying contract. Further, Section 4 of the Statute of Frauds Act 1677 requires guarantees to be in writing and signed by all parties.

Hybrid securities

In reality some securities are in fact a hybrid between an On Demand Bond and a guarantee in that they are conditional and require some proof of some primary default under the underlying construction contract before they will pay out.

A typical example in the UK is the ABI Model Form of Bond. Clause 1 provides that:

“The Guarantor guarantees to the Employer that in the event of a breach of Contract by the Contractor the Guarantor shall subject to the provisions of the Guarantee Bond satisfy and discharge the losses and damages sustained by the Employer as established and ascertained pursuant to and in accordance with the provision of or by reference to the Contract and taking into account all sums due or to become due to the Contractor”. [Emphasis added]

It is important not to mistake a conditional bond such as the ABI Bond for an unconditional On Demand Bond when you are offered one and to seek legal advice if you are unsure of the position. The difference could be a couple of years, or even more, between when you make a claim and when the monies are paid to you.

Setting up properly: what should I look out for?

Having reviewed the key differences between the type of securities you could be offered (and why they matter), we now set out a check list of issues you may wish to check at the outset to avoid issues later on. Questions to ask include:

- Do I need a security given the cost?

- What have I been provided with?

- Should I incorporate any safeguards on when a call can be made?

- Who is the security from, and do they have any money?

- Are there any glaring inconsistencies between my security and my construction contract?

- What are the dispute resolution procedures for my security, and do they work with those in my underlying construction contract?

- What governing law and/or jurisdiction is provided for?

- Where is any counter security located?

Do I need a security?

The cost of securities is undoubtedly increasing in the current economic environment. With the costs being what they are, it is likely that the cost of providing a security will be added in some way or form to the contract price offered. It is therefore worth considering if there are less costly alternative securities available (for example a parent company guarantee instead of an On Demand Bond). If the financial status of the contractor is good and there is a long-term relationship, is a security needed at all? Likewise, if a contractor can only get a very expensive security is that an indicator that its financial position is not as strong as you would ideally like it to be?

What have I been offered?

As emphasised above, labels are not always correct or helpful and a security must always be analysed as a whole. Indicators that a security is of a particular type can include:

|

Feature |

Suggests? |

|

Incorporation of the URDG11 |

May suggest an On Demand Bond |

|

Conclusive evidence clause |

May suggest an On Demand Bond |

|

Issued by a Guarantor instead of a financial institution |

May suggest it is a guarantee |

|

Wording suggests the bank’s liability is not secondary |

Suggests it is a guarantee |

|

No exclusion of Guarantor’s equitable defences |

Suggests it is a guarantee |

|

Parties in different jurisdictions |

May suggest an On Demand Bond |

Are safeguards required?

Safeguards for On Demand Bonds are also worth considering particularly if you are the person offering that On Demand Bond, do not have a long-term relationship with the employer, and/or the employer is an SPV. These safeguards could include:

- Requiring additional documents to be presented with any demand;

- Providing as to who is required to sign any demand;

- Considering a hybrid form. For example, in the United Kingdom an adjudication decision could be required before a call could be made; and

- Incorporating the URDG 758 a set of rules published by the ICC which include standard safeguards.12

Who is the security from?

If a bondsman has offered the security, then you should always check their financial strength. Never accept a security without doing your due diligence first. This applies to contingent as well as on demand securities. Ultimately, your security is only worth as much as the company or person who is offering it. In relation to a Parent Company Guarantee, does that parent company have any assets? Further, what jurisdiction are they located in? This is essential to check because it may not be easy to trace if the has assets if they are domiciled in some jurisdictions. How easy would it be to transfer assets out of that jurisdiction notwithstanding the existence of the security? Finally, how easy is it to enforce judgments in that jurisdiction? If it is very difficult, how expensive will making a claim be in reality?

Check for, and avoid, inconsistencies

Huge problems can be caused where there are inconsistencies between the terms of a bond or guarantee and the terms of an underlying contract. This can give rise to disputes and complicate matters hugely. Common drafting errors or oversights include inconsistent terms regarding the expiry or termination or discharge of the bond. For example, in Simon Carves Ltd v Ensus UK Ltd13 a bond provided for a long stop expiry date of 31 August 2020. However, the underlying ICE Contract provided that a bond shall be null and void and shall be returned upon the acceptance certificate being issued. Akenhead J held in paragraph 37 of his judgment that upon issuance of the Acceptance Certificate in February 2020 (i.e., earlier than the long stop expiry date) the bond must be treated as null and void. In other words, the underlying contract terms prevailed.

Inconsistent dispute resolution provisions are also problematic. For example, what happens if the underlying contract provides for adjudication or arbitration but the bond or guarantee itself is silent? This can result in a jurisdictional challenge if a party seeks to refer the dispute about the bond or the guarantee to the arbitration together with the dispute under the underlying building contract for convenience. The tribunal will then have to ascertain whether it has jurisdiction which will depend in part on how widely the arbitration clause is drafted. All of these unnecessary arguments can be avoided if proper thought is given to the dispute resolution provisions of both the underlying contract and the bond or guarantee during pre-contractual negotiations.

Governing law and jurisdiction clauses

The governing law and forum for dispute resolution can make a material difference to the availability of injunctive relief and grounds for resisting a bond call. Some of the differences are set out in the table below.

|

Governing law |

Position |

|

English and Hong Kong law

|

An injunction will only be granted if the Demand is fraudulent or precluded by the terms of the underlying contract.14

|

|

Australian law

|

You may get an injunction to enforce a promise not to call on a bond.15 |

|

Singapore law |

“Unconscionability” is a further established ground for restraining a bond call.16 |

|

UAE Law 417(2) of the UAE Federal Commercial Law No. 18/1993 |

This allows the court to place an attachment order on the draw down sum “in exceptional circumstances” if there are “serious and certain reasons for the request” (for example if there is evidence that sums claimed are not due and/or significant payments to the Contractor are outstanding). |

As to why the governing law is important, this is illustrated by the Singaporean case Shanghai Electric Group Co Ltd v PT Merak Energi Indonesia17 where the Singapore court applied English law grounds for determining whether to grant an injunction only because the bond was expressly governed by English law. If Singaporean law had applied the call may have successfully been resisted on the grounds of unconscionability which is a much lower threshold to reach than fraud.

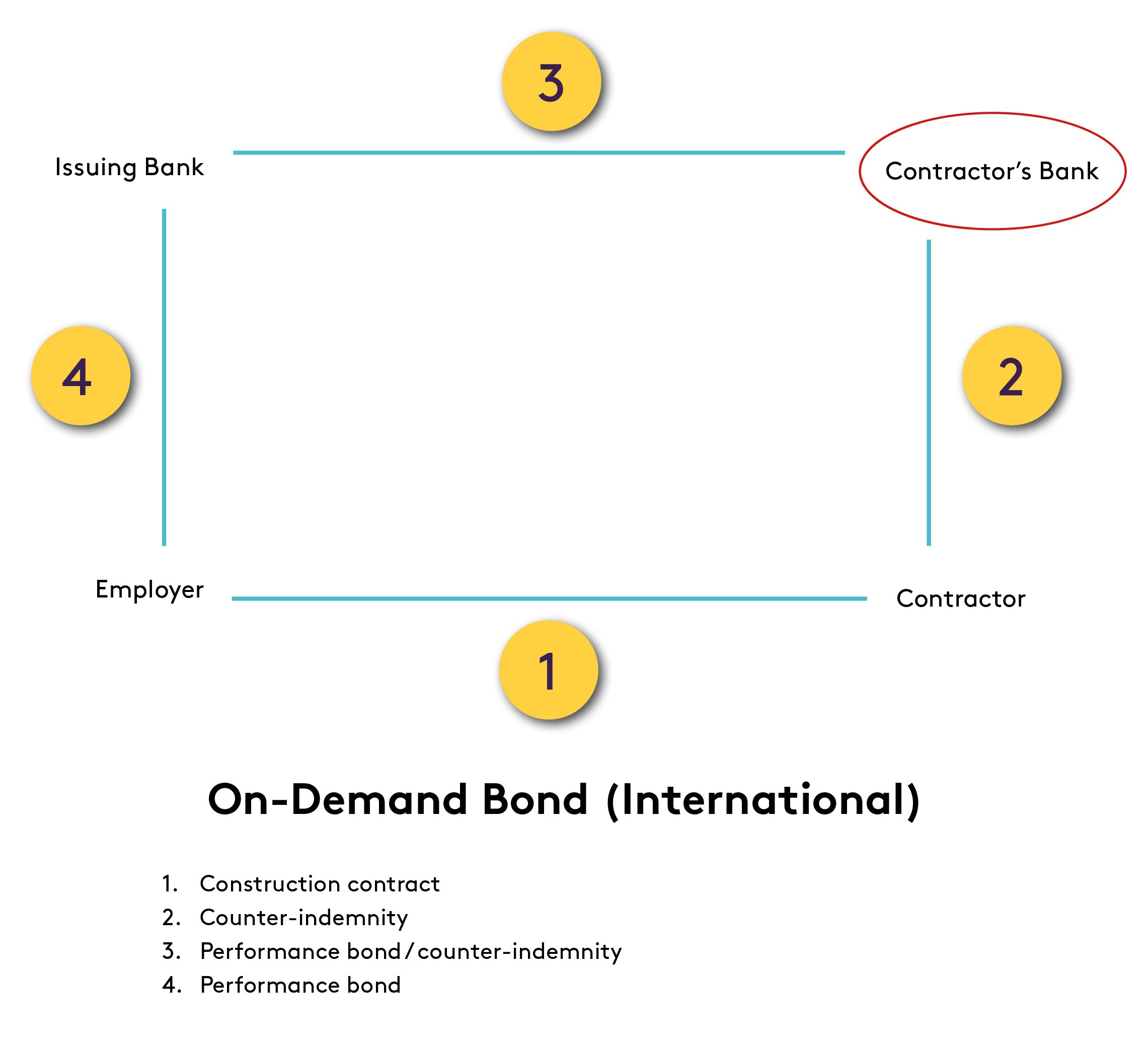

Where is the counter security located?

Finally, in the international context, it is also important to take note of which country the issuing bank for any counter security is located in. What is their attitude on stopping calls on securities via injunctions? A diagram of a typical On Demand Bond counter security structure is set out below.

The case of National Development Company Ltd v Banco Santander SA18 illustrates this. In that case the Brazilian main contractor for a road project in Trinidad became insolvent. They had issued Standby Letters of Credit (valued at circa US$100 million in total) to the employer that were subject to English law and the jurisdiction of the English courts. However, the counter-indemnity in the diagram above was issued by Brazilian banks to English banks. An injunction was obtained in the Brazilian courts against the Brazilian banks, and they later extended that injunction to cover the English banks as well.

The English banks were concerned they wouldn’t get paid out and the Brazilian banks were conscious they didn’t have enough money in the bank to get repaid due to the contractor’s insolvency. Eventually, the English courts ordered the banks to pay out, but additional costs were incurred in enforcement, and delay was encountered in getting the funds paid out. The case illustrates the English courts’ robust approach for enforcing on demand securities but equally, it also underlines the dangers of having counter-indemnities issued by banks in jurisdictions which may not be as robust.

What to do when things go downhill

So, what should parties consider when it looks like it may be necessary to call on a security?

On Demand Bonds: the employer’s perspective

As an employer, perhaps the most important thing to check is the expiry date on your On Demand Bond. Is the expiry date absolutely clear? Second, you need to establish what grounds allow a call under the construction contract in question. Work backwards from when you think you may need to make the call and ensure that all notices under the underlying construction contract have been issued in good time and follow the contract wording to the letter.

Formalities in relation to demands on an On Demand Bond must be strictly observed. Check and double check that the wording in your demand is an exact match to what is required. Do not paraphrase. Consider also who is required to sign the original demand. Are they in the same country? Is a company seal required? Is the demand on the correct letterhead? All these seem like basics but if they are wrong payment may not be made. If time is tight and the security is about to expire, neglecting the basics could be fatal to any claim.

Finally, consider the location of the institution you must serve on. Is it always open, is it easy to find or has it moved? A process server is also worth consideration particularly if the institution you are calling on is in another jurisdiction or has a history of being (deliberately) reluctant to accept service.

In other words, don’t leave anything to chance.

On Demand Bonds: a contractor’s perspective

The first message that someone seeking to prevent a call under English law needs to hear is that it may be very difficult to stop if the security is a pure On Demand Bond. As a result, even if you are also exploring the possibility of obtaining an injunction against the beneficiary under the underlying construction contract, you need to deal with the underlying claim as proactively as possible. Is paying some Liquidated Damages, but not all, as a middle ground preferable to a call being made for the full amount?

If an On Demand Bond is about to expire, consider extending it. Don’t play “who blinks first” in relation to an extension particularly if the cost of a call being made will far outweigh the damage to your business of extending a security. For example, your ability to provide bonds for future tenders may be negatively impacted.

Guarantees/Conditional Bonds: the employer’s considerations

For Hybrid Bonds more thought is required before an Employer before a call can be made as more is required than just a simple demand. As such, careful consideration needs to be prepared taking the exact wording of what is required. Recent case law on ABI bonds requiring ascertainment of loss includes:

- Ziggurat (Clairemont Place) LLP v HCC International Insurance Company Plc.19 Coulson J confirmed at paragraph 55 that, in the event of an insolvency or termination, it suffices to operate the contractual procedure for calculating the post-termination account before making a call. This would include the mechanisms in clause 8.7 of JCT Contracts.

- Yuanda (UK) Company Ltd v Multiplex Construction Europe Ltd & Another.20 Fraser J held at paragraphs 70-83 that an adjudication decision awarding liquidated and ascertained damages (“LADs”) sufficed to allow a call to be made but not a mere payment notice or demand for LADs. Taking this into account in terms of timing could be crucial if the security is about to expire as you would need to ensure that your adjudication decision was awarded in good time to allow calls still to be made.

In relation to a guarantee, an employer first needs to establish a breach of the underlying primary obligations by adjudication, arbitration or litigation as applicable before they can obtain payment from the Guarantor.

The result is that calling on a Conditional Bond or Guarantee may not be a quick fix. For example, in Energy Works (Hull) Ltd v MW High Tech Projects UK Ltd & Others,21 it took 3.5 years from issuing a claim in July 2019 to final judgment being obtained in December 2022 before payment under a Parent Company Guarantee could be unlocked.

Guarantees/Conditional Bonds: a contractor’s considerations

As to a contractor’s considerations, they need to consider the terms of any indemnity agreement with the bondsman or guarantor. Does the contractor have enough resources or cashflow to reimburse the bondsman or guarantor in respect of the drawdown sums? When does the reimbursement have to be made? Does the indemnity require payment into the bonds or guarantees in advance even if payment is made to the beneficiary for several years?

It is also worth considering in advance if there is any room for a commercial resolution. Could you extend the expiry of the date of the Hybrid Bond or the guarantee, perhaps make a payment into court or if proceedings have not yet commenced, make an on account payment to the employer into a ringfenced account? If the alternative is a call being made that will result in you having to pay the cash into the bondsman’s account to hold as security, all options are worth considering.

What if there has been a wrongful call?

Finally, it is worth considering what your entitlements are under English law if an employer wrongfully calls on an On Demand Bond and the money is paid out to them. The primary remedy is an account in between the parties and repayment by the employer of wrongfully drawn down sums.22 However, sometimes other remedies are sought such as damages for increased financing costs or loss of opportunities or revenue on the grounds of a breach of contract. Such claims are generally difficult because there is no implied duty of good faith or duty otherwise not to call on the bond.23 There is also no implied term requiring a demand to have a contractual basis as the bond can validly be called despite a genuine dispute over the claims.24 Further, proving causation and the quantum of any financial losses arising from a bond call is often difficult and may require expert accounting evidence.

Conclusion

In the current economic environment, it is more crucial than ever to check that you know what you have been given by way of security, or indeed what you have given, at the outset of a project. If things start to go downhill and a call is likely, then you must do your homework sooner rather than later to ensure that you follow the steps required and have enough time to call on the security before it expires. Likewise, if you want to prevent a call, or mitigate its potential effects, acting sensibly and engaging with the underlying claims sooner rather than later is essential. All too often advice is not sought until too late on in the process of making a call, or resisting one, resulting in the position becoming much more complex and expensive than it otherwise might be.

- 1. By Claire King. With thanks to Mathias Cheung of Atkin Chambers who delivered a Fenwick Elliott webinar on the same topic with Claire King.

- 2. 7th Edition, by Mrs Justice Andrews and Richard Millett KC.

- 3. [1978] 1 QB 159.

- 4. [1996] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 345.

- 5. [2007] EWHC 3508 (QB).

- 6. [2011] EWHC 657 (TCC).

- 7. [2013] EWHC 3201 (TCC).

- 8. [2015] EWHC 949 (TCC).

- 9. 7th Edition, by Mrs Justice Andrews and Richard Millett KC.

- 10. [2010] EWHC 2443 (Ch).

- 11. Uniform Rules for Demand Guarantees as published by the ICC.

- 12. Article 15(a) for example provides that a Demand is supported by a statement by the beneficiary indicating in what respect the applicant is in breach of his obligations under the underlying relationship. The statement may be in the Demand itself or in a separate signed document accompanying or identifying the Demand.

- 13. [2011] EWHC 657 (TCC).

- 14. See MW High Tech Projects UK Ltd v Biffa Waste Services Ltd [2015] EWHC 949 (TCC) at 33-36.

- 15. See Reed Construction Services Pty Ltd v Kheng Seng (Australia) Pty Ltd (1999) 15 BCL 158 at 164.

- 16. See JBE Properties Pte Ltd v Gammon Pte Ltd [2011] 2 SLR 47 at [10].

- 17. [2010] 2 SLR 329.

- 18. [2017] EWCA Civ 27.

- 19. [2017] EWHC 3286 (TCC).

- 20. [2020] EWHC 468 (TCC).

- 21. [2022] EWHC 3275 (TCC).

- 22. See Cargill International SA v Bangladesh Sugar & Food Industries Corp [1998] 1 WLR 461 (Staughton LJ).

- 23. Costain International v Davey McKee (London) Ltd CA unreported 26 November 1990.

- 24. See MW High Tech Projects UK Ltd v Biffa Waste Services Ltd [2015] EWHC 949 (TCC) at 36.